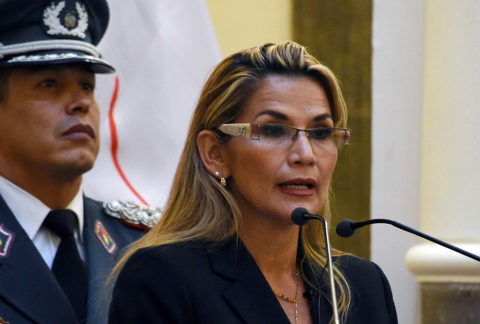

Due to concerns about future projects in Latin America, Russia has reaffirmed its willingness to cooperate with Bolivia’s Interim President Jeanine Áñez, who promised to respect the ruling of the Supreme Electoral Court to hold elections in May 2020. The relations between the two countries involve investments worth over $1.5 billion in Bolivia’s defense, gas, and nuclear energy sectors, which were agreed upon in the later years of former President Evo Morales’ term (2006-2019.)

Although the Kremlin was one of the first to voice its concern about Morales’ resignation in November 2019, it now distances itself from the former president in an attempt to protect its interests in Bolivia.

Russian President Vladimir Putin said in November that no matter who comes to power in Bolivia, he hoped that the new government would remain interested in expanding relations with Russia. “We are ready to cooperate with the authorities, who will be lawfully elected by their country’s people,” he added.

“Moscow, which supports authoritarian regimes [like Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela], stepped away from Morales and tries to safeguard its interests in the Andean country,” Iliana Rodríguez Santibáñez, deputy director of the Regional Department of Law at Monterrey Institute of Technology in Mexico, told Diálogo. “Preserving their presence in the country allows them to interfere in political, economic, and social aspects in the region.”

After nationalizing natural resources in 2006, Morales opened the doors to Russian investments. Russian state-run corporation Rosatom, with more than 360 subsidiaries producing nuclear energy and weapons worldwide, signed a memorandum of cooperation with Morales for lithium mining, and is building the Center for Research and Development in Nuclear Technology in El Alto, La Paz department, worth $300 million and expected to start operations in 2021.

The corporation’s agreements are powerful tools for political leverage. Rosatom’s former director Sergey Kiriyenko is the Putin government’s first deputy chief of staff, responsible for Russia’s internal affairs.

The Russian news portal Proyecto says that Rosatom has been intervening in elections in at least 10 Russian cities since 2016. “The company’s ability to manage election campaigns in such a secretive way that no media outlet would be able to detect it for five months could be useful in Latin America, but they were not able to influence the results of the 2019 Bolivian elections, thanks to street protests,” Proyecto reports.

Rosatom has been involved in high-profile scandals. In August 2019, the failed test of a “new weapon” caused a nuclear explosion in the Arkhangelsk region, in northeast Russia, leaving an initial death toll of five and a radiation level 16 times higher than normal. It was only one week later that authorities finally asked the inhabitants to leave the area, said Peruvian daily newspaper La República.

In 2017, a South African court ruled that the $76 billion agreement with Rosatom to build nuclear plants was illegal, because it had been signed without consulting the parliament. Uganda, Rwanda, and Ghana, among other countries, are reviewing similar agreements, said British daily newspaper The Guardian.

Another Russian corporation present in Bolivia is Helicópteros Rusos, a subsidiary of state-run Rostech that expects to sell aircraft to the Bolivian Army. In addition, Russian state-run company Gazprom has offered to search for underground water and to invest $1.22 billion to start explorations in the Vitiacua field, Chuquisaca department, which can produce 424 million cubic feet a day of natural gas, said national company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos. The Russian company is among the world’s 20 highest polluting companies, ranking third in the list, said The Guardian.

“A privileged group managed the resources of the country’s General Treasury and squandered money on public works that didn’t bring any economic and social development,” said José Luis Parada, Bolivia’s minister of Economy and Public Finance. “Evo Morales had no idea of what his ministers were doing. In his 14 years [of government], he never knew what was happening in the economy, he didn’t know about the five-year long budget deficit, he didn’t know about the four-year long trade deficit; that’s why he continued to offer deals here and there,” he said.