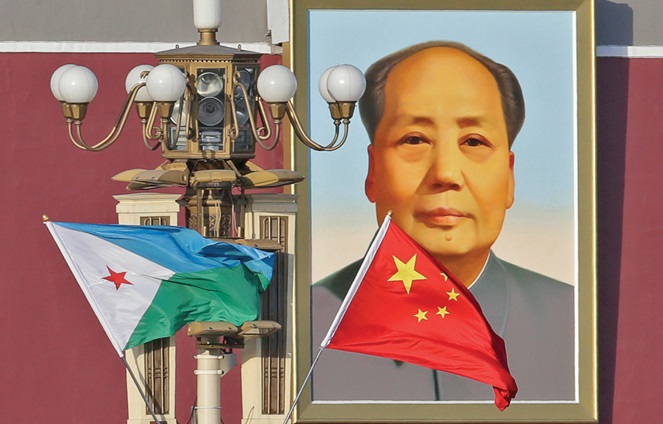

On the 90th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), August 1, 2017, China opened its first overseas naval base in the eastern African country of Djibouti. Questions regarding China’s future intentions quickly ensued: Would China open another such facility? If so, where and how soon? Though interest in China’s global military ambitions grew, answers were not forthcoming. When asked about plans to establish additional naval bases or operate beyond China’s own borders, Chinese government officials, officers in the PLA, and China’s think tank scholars routinely demurred. Analysts were left to monitor for any signs of China’s future intentions. Global security affairs observers could only speculate about China’s next steps.

Yet in the short time that followed, much has changed: China’s strategists now openly express a desire for access and presence. They discuss options, debate the merits of various approaches, and stress that overseas locations will inevitably be necessary to secure their country’s ever expanding interests. So, if Chinese analysts and military planners are now discussing China’s global approach to access and posture more openly, what are they saying? What criteria guide their thinking? What types of facilities are being considered? Are they focused on a specific part of the globe? An emerging body of research by Western scholars of Chinese military affairs leverages Chinese military and academic writings to provide insight into Chinese thinking on several of these questions.

Alternative forms of access

The data seems to suggest that the dedicated military facility China opened in Djibouti may not be representative of China’s approach to access and posture moving forward. Recent research by Dr. Isaac Kardon, Conor Kennedy, and Dr. Peter Dutton of the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute suggests that China’s military and civilian planners are less focused on the pursuit of an extensive network of overt military facilities, and more on alternative forms of access.

Kardon and his colleagues suggest that a consensus is emerging among China’s community of strategic thinkers that the best path to global military access is one that emphasizes flexibility and leverages the presence that Chinese enterprises have established at commercial ports worldwide to provide the logistical support necessary to enable distant naval operations. In short, while China’s planners have studied the U.S. model of permanent, forward-deployed military bases that enable global power projection, at present they don’t seem bent on recreating it. Rather, the literature suggests a network of access points, or “overseas strategic support points” that will enable a more limited set of operational activities: securing key maritime chokepoints and sea lines of communication, escorting civilian shipping, protecting maritime rights, as well as conducting counterpiracy operations, non-combatant evacuation operations, and perhaps limited maritime interdiction operations.

In addition to discussing the value that commercial, or dual-use “support points” will have in China’s approach to developing military access and posture moving forward, Chinese planners also debate the criteria for selecting such locations. In testimony before the 2020 and 2019 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Kardon noted that Chinese analysts seek access in many of the same locations that their counterparts in other navies would. China’s analysts appear to favor locations that are near strategic chokepoints or areas where crises tend to erupt, offer favorable environmental conditions for the berthing of ships, are easy to defend, and are located in well-governed states that are positively inclined toward Beijing.

Leveraging ports

Kardon, however, notes an additional consideration, one that is particular to China’s approach and that raises questions regarding the future trajectory of China’s efforts to establish access: Chinese planners appear focused on leveraging the growing number of ports that are owned or operated by Chinese state-directed firms. According to Kardon, this preference builds on the PLA Navy’s operational experience to date (its counterpiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden have, to a great extent, been supported by commercial husbanding agreements), and leverages China’s status as a global leader in the construction and operation of commercial port facilities worldwide.

By Kardon’s count, Chinese state-directed enterprises own or operate at least one terminal in 59 ports across the globe, and have interests in 18 port projects in the Western Hemisphere alone, several of which are located near key geostrategic chokepoints such as the Panama Canal. To the extent that Chinese firms exercise control over the operations of such ports, they would enjoy significant leeway to grant access to naval vessels, arrange for the prepositioning and storage of supplies, and facilitate the maintenance and transshipment of goods and personnel to enable forward deployed ships to operate for extended periods of time, and at a distance from their homeland.

To be sure, some countries would decline allowing such activities, but Kardon rightly notes that such arrangements would likely be feasible if China’s military were seen to be conducting legitimate or justifiable military operations or that address the host nation’s security concerns. Additionally, such access would likely be possible in nations where low degrees of transparency are the norm with respect to contracting and government oversight, or in countries where China possesses a significant amount of leverage due to its trade, investment, and lending relationship with the nation hosting a given port.

A series of concentric zones

China’s presence at commercial ports across the globe gives China’s leadership broad options for developing such access, but Western experts of Chinese security affairs suggest China’s priority, for now, remains where one would expect: in the vicinity of the homeland. In testimony to the 2020 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, U.S. Navy Admiral (ret.) Dennis C. Blair, former U.S. director of National Intelligence and commander of U.S. Pacific Command, noted that Chinese strategic thinkers see the world as a series of concentric zones. The first, and most important, begins with China itself, and consists of the areas to the immediate north, south, east, and west of the country, to include China’s eastern and southern maritime periphery. As Adm. Blair noted, China’s immediate periphery absorbs a majority of the country’s planning, programming, exercising, and budgeting. Until the status of Taiwan is resolved, this is unlikely to change.

However, the next most important region for China’s strategic thinkers, where China’s overseas interests begin in earnest, is central and south Asia, from the Middle East through the Indian Ocean to Southeast Asia. This zone is home to the chokepoints through which much of China’s energy imports flow, to include the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, and the Suez Canal. The region is host to the PLA’s highest-profile series of overseas operations, the counterpiracy and escort operations the PLA Navy has been conducting under the auspices of the United Nations since 2008, and thus, unsurprisingly, is the geographic area of greatest focus in discussions of potential additional access and posture locations. While the establishment of a “support facility” in Djibouti alleviated some of the PLA Navy’s concerns over China’s ability to support continued operations in the area, China’s military planners appear to believe that additional access locations will be necessary to secure both the eastern and western end of the route that China refers to as its “maritime lifeline.”

Though leaders in Beijing may want better options when seeking to protect China’s global interests, and China’s planners consider a variety of ways China might establish access and posture to provide those options, it is not a foregone conclusion that China’s attempts to enhance its global military posture will succeed. There are several factors that may impede Beijing’s attempt to develop a network of facilities capable of enabling sustained or even periodic military operations outside the Asia-Pacific.

Chief among these are the views of nations worldwide regarding the presence of the Chinese military on their soil, in their periphery, or adjacent to strategically significant maritime chokepoints. At present, with the exception of North Korea, with whom China maintains a treaty of “Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance,” China has no military alliances that could quickly or easily support the establishment of a military-use or even dual-use PLA facility on foreign soil. While experts, such as Kardon, have pointed out that there exists language that provides for the status of forces among members of the Beijing-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization and agreements that facilitate presence to support exercises with the Russian military, Djibouti aside, no such arrangements exist that would facilitate the permanent presence of PLA soldiers on foreign soil.

Chinese boots on foreign soil

Observers note that China could identify a willing partner and initiate discussions, but the list of countries worldwide that would be amenable to such at present is short. Nations generally take a dim view of requests to host foreign military forces on their soil, agreeing to do so only when they deem it to be in their interests or otherwise feel compelled to oblige. Countries that have historical experience with colonization or foreign occupation view the idea even more critically. Given the current level of concern in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and India regarding Beijing’s intentions, nations willing to entertain the prospect of Chinese boots on their soil would have to be willing to face the resulting political, diplomatic, and economic repercussions that might result from such a choice.

Without a doubt, some countries would consider doing so, especially those that are currently isolated from and disenchanted with the Western-led liberal international order. However, should China announce the opening of yet another foreign military base or dual-use access point, the world’s major powers would likely feel compelled to respond. While geopolitical decisions are not always the function of a logical cost-benefits analysis, it stands to reason that leaders worldwide would proceed cautiously when considering moves that might trigger a response from the world’s most powerful militaries and the leaders of nations that still largely dictate the conduct of global political and economic affairs. Would such a decision, on the whole, benefit or harm the country that agreed to provide the PLA with access equivalent to a forward deployed naval base?

While China, at present, is more likely to pursue such access on a rotational basis and via commercial arrangements in locations where Chinese state-directed companies maintain an established presence, even that route comes with significant financial and reputational costs. Overt attempts to militarize commercial facilities, should they impact operations or the flow of goods and services, could jeopardize the existing commercial interests of the nation hosting the facility and the others that use it.

Such attempts would also impose a broad reputational cost on China and the Chinese companies that have spent the better part of three decades establishing a presence in commercial ports and logistics enterprises around the world. For decades, China’s leaders have consistently pledged that their interests are solely commercial in nature. Actions that demonstrate otherwise could damage Beijing’s credibility beyond repair, and put China’s access to commercial ports across the globe at risk. When faced with a global contingency, officials in Beijing might find such an opportunity cost acceptable. It is hard to believe they would do so, short of facing scenarios that would put China’s core national interests at risk.

It is clear from China’s military and academic writings that the views of China’s planners and strategists have evolved. The fact that Chinese security analysts are openly discussing China’s need for access and posture is in itself evidence of this, and is a relatively new development in Chinese security affairs. If history is any guide, the views of China’s strategic thinkers will continue to adapt as China’s interests expand, the expeditionary capabilities of its Navy and Marine Corps grow, and the international security environment shifts in response to these developments. If the views of China’s planners are any guide, the world would do well to watch and keep an open mind as to how China will arrange for its next posture location: China opened its base in Djibouti with a press release, a flag-raising ceremony, and the deployment of ships and several hundred service members to mark the occasion. Next time around, it is unlikely Beijing will be so obvious.