The Darién jungle “is not a migratory route,” warns Samira Gozaine, director of Panama’s National Migration Service (SNM). As such, raising awareness about the reality of migrants who cross the dangerous jungle between Colombia and Panama, exposing themselves to transnational drug and human trafficking networks, robbery, rape, and other crimes, is a priority.

Diálogo spoke with Director Gozaine about the problems that irregular migration poses and the importance of the international community’s participation in discouraging it.

Diálogo: What is your main challenge as the head of the SNM?

Samira Gozaine, director of Panama’s National Migration Service: The illegal migration that enters through our border with Colombia through the Darién Gap. In 2016 we were talking about a migration crisis with 14 000 people crossing the jungle that year, and so far this year [2023] we have more than 250 000 people. It’s important that we use our resources to contain migration and to provide information adjusted to reality, which is what I believe could help this situation the most, because most of the people who arrive, for example from Colombia, have stated that if they had known the reality of what they would face in the jungle, they would not have migrated that way.

Diálogo: How was the SNM prepared to face illegal migration?

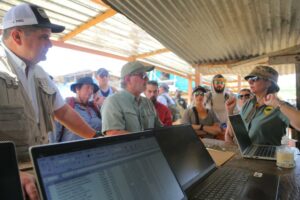

Director Gozaine: Unfortunately this human tragedy took us by surprise in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. We had to request more training for our staff and infrastructure, and on the fly, make decisions to change our institutional dynamics as we fulfill other administrative and security functions. We are a small institution with 1,600 officers to cover all the formal checkpoints in the country, and with the support of Public Security Minister Juan Pino, a team was formed in coordination with the National Border Service [SENAFRONT], the National Air and Naval Service [SENAN], the National Police, and the SNM to jointly address this problem.

Diálogo: Organized crime thrives not only on drug trafficking but also on human trafficking. What is your greatest concern in this regard?

Director Gozaine: The concern is that international organizations, especially the Human Mobility Group [an operational coordination team that the United Nations System and its partners created to provide a humanitarian response to illegal migrants] continues to talk about the right of human mobility — regardless of whether it is illegal and dangerous to the human rights of the individuals who are doing it. In addition, it is organized crime that leads this movement of people and it has become an increasingly lucrative business. We have heard countless stories of migrants in transit who exposed their lives walking through the jungle, who were sold “tourist packages” to cross the jungle and who were told that it was a safe route, that visas were not required, etc. Today we have a massive migration of human beings with their families, where 25 to 30 percent are minors, and of those, 50 percent are under five years old.

There is nothing humanitarian in continuing to let transitory migrants cross and allow organized crime to profit and receive funds to help them perpetuate their other criminal activities. The Darién Gap should be kept as a buffer, but the same Clan del Golfo opened it for us and this illegal migration should not be allowed to continue. I am not criminalizing migration but the traffickers who use the need of a human being to benefit and profit, that is why the countries of the region need to talk and define safe ways and means of migration.

Diálogo: Organized crime is benefiting from illegal migration, especially with children. What is your perspective on this situation?

Director Gozaine: This situation is very dangerous because there is no way of knowing if the minors who come are the children of the people who bring them. We have had cases in which minors have been abandoned in the jungle, given to others to carry them on, found next to the corpses of their parents, or sold by them to pay for the trip.

Diálogo: You have reiterated Panama’s commitment to discourage illegal migration, reaffirming the government’s message that the Darién jungle is not a migratory route. What actions are being taken in this regard?

Director Gozaine: The budget we have earmarked does not amount to what we have spent on humanitarian attention to this migrant population. We have the will to do what is necessary to discourage migration, however we require support, and the assistance that international organizations have given us has been limited. We do not have all the capabilities, but with what we have we are making a great effort. For example, the SENAFRONT has detained a large number of human traffickers at the border and rescued hundreds of people. Daily air rescues have increased fivefold so far this year, and we have begun to deport and repatriate, for example, some Colombians who have a police record.

Diálogo: What international collaboration have you received in dealing with this situation?

Director Gozaine: The help from the U.S. Embassy and all the agencies that work there has been very positive, since they have donated equipment for biometrics, provided resources to SENAFRONT with logistics and trucks and helicopter support to the SENAN to carry out rescues in Darién, and in general they have supported us to fight organized crime in the area head-on.

From the international community in general, we have received help as far as water purifiers for the shelters, children’s canteens, help with some food kits, cleaning kits, but the help has been very limited. For example, last year we asked for international assistance to repatriate more than 10,000 Venezuelans who wanted to return to their country, and we didn’t manage to get it. We received donations from the Catholic, Evangelical, and Protestant churches and from private individuals.

Diálogo: What is the importance of the “Amber Alert” for illegal migration?

Director Gozaine: The “Amber Alert” is an important tool to detect whether there are children abducted from their countries of origin within the migratory flow through the Darién jungle. We have a commission formed by several ministries and institutions that have to do with security to help us with the necessary information and to be able to detect if any minor who is in our country could have been kidnapped and help in their repatriation. We do biometrics on everyone who crosses the Darién.

Diálogo: What is the environmental damage in the Darién Gap, declared a World Heritage Site in 1981 and a Biosphere Reserve in 1983?

Director Gozaine: More than half a million people have crossed the Darién in the last four years, and we still don’t really know the magnitude of the environmental damage caused, since the migrants have left all kinds of garbage in the jungle, such as disposable diapers, cans, shoes, clothes, etc., that would take centuries to decompose.