Since the end of the Cold War, changes in the context of what used to be called “war” have transformed military thinking around the world. The beginning of the 1990s, marked by the certainty that history was writing a new page in the evolution of humanity, brought to military science the challenge of reflection and adjustment to the new scenario of international relations.

The phenomenon of globalization, with the breaking down of commercial frontiers and the consequent approximation of states, eliminated the old vision of political bipolarity and established new paradigms of multinational relationships.

In this context, although some literature provides an opinion to the contrary, Clausewitz’s thought seems to have an even more decisive impact on the understanding of the use of the military expression of the national power of states. The premise of this assertion lies in the perception of the growing importance of the use of small fractions in confrontations, the selective use of weapons, the correct communication of actions at all levels, the search for the reduction of “collateral effects,” and, above all, the faithful understanding of the desired end-state established by military strategy.1 This, in the last analysis, translates political thought to the operational and tactical levels that will manage (plan and conduct) armed violence. In short, politics has come closer to military tactics, and the latter must understand them than ever before.

If before the analysis of the spectrum of conflicts was strongly summarized in the capacity of the contending states to use war power (stricto sensu), it is now necessary to understand the psychosocial conditions and the dynamics of communication inside and outside the conflict.2

Military science began to perceive conflict in its three dimensions: physical, human, and informational.3

Based on these perceptions, the School for Officers Improvement (EsAO) has developed a broad discussion with its faculty and students, in order to give scientific treatment to the last 30 years of operations of the Brazilian Land Force and to align the doctrinal knowledge of Offensive Operations and Defensive Operations with the recent Operations of Cooperation and Coordination with Agencies (OCCA).

The desired end state, for the next two years, is that OCCA will be perfectly aligned with the “war” doctrine and that the EsAO student captain will broaden his tools for planning and conducting operations at the tactical level.

U.S. TRADOC: The “war” of the future

Recently, at the initiative of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare (TP 525-92) was published with new concepts of this complex “new terrain” in which land forces operate today. In identifying the new threats, expected by the mid-2050s, the document cites:

Doctrine and Capabilities Expansion

Our adversaries are already endeavoring to develop new methods and new means to challenge the U.S. These efforts will only continue and attenuate through 2050. We can expect to face:

- Threats in multiple domains;

- Operations in complex terrain, including dense urban areas and even megacities;

- Hybrid strategies/”Gray Zone” operations;

- Weapons of Mass Destruction;

- Sophisticated anti-access/area denial complexes;

- New weapons, taking advantage of technological advances (robotics, autonomy, AI, cybernetics, space area, hypersonic technology, etc.);

Information as a decisive weapon.4

In this new scenario, the basic operations of the world’s land forces began to aggregate, besides offensive and defensive, also Cooperation and Coordination Operations. This new military concept, in its broadest sense, includes in the planning and conduct of maneuvers national and international agencies, non-governmental organizations, national or multinational companies, and civilians of the most diverse origins.

Faced with the challenge of Operation Desert Storm (1991) and the post-9/11 experiences (2001), the Americans perceived the various nuances of their new enemies and their remarkable capacity to mold themselves to the most diverse environments. These new spaces, now surrounded by issues that gained prominence in the context of global political-ideological change (environment, minority rights, protection of civilians, responsibility to protect, etc.), favored the proliferation and strengthening of hybrid forms of combat and the near break with the paradigm of “linear warfare.

It was necessary, then, to deeply study the successes and failures of operations, at their various levels, identifying the emergent changes, not only in techniques and tactics, but, and fundamentally, in the way of thinking about the new model, reformulating the science of war in the 21st century.

It is noteworthy that this new perception was motivated by the very structure and mission of the Armed Forces of the USA, which are instruments of dissuasion for the maintenance of the permanent national objectives of the largest world economy. The U.S. Constitution does not allow them to act internally on issues similar to those found around the world and that permeate the current combats: arms trafficking, drug trafficking, human trafficking, active and passive corruption at different levels of public power, conflict between parallel sectors to the established government, public security (lato sensu), etc.

Colombia: The “Damascus Doctrine

At the regional level, motivated by the military rapprochement with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Colombia launched its new doctrine in 2016, baptized the “Damascus Doctrine”.

Since 2010, with the downward trend in confrontations with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the need for change was emerging, especially due to the constant questioning by national and international human rights representatives about the military’s performance techniques and its effective contribution to the reconciliation and reintegration processes of the victims of the conflict.5 As of 2016, the process of disarmament and demobilization of the former guerrillas began and a greater participation of the Colombian National Army (ENC) in non-armed missions, similar to those of the National Police and civilian agencies linked to socioeconomic projects.

At the heart of the agreement to transform the armed forces, in addition to the country’s political level interests, was the strengthening of the legality of internal actions carried out since the 1960s, now in the framework of NATO standards, modulated for the 21st century.

While making the new doctrine public, in August 2016, the then Commander of the ENC, General Alberto José Mejía, referred to the proposed transformation as follows:

[A] most important one in a century: transcend security operations – which will be maintained, even refortified – and achieve social stability and governability through integral service to communities. We are going from offensive and defensive military activities to two new models: one of stability, which seeks to consolidate areas in order to be close to the civilian population and state entities; and the second, the model to ensure governability through social and humanitarian aid, as has been seen in recent days. This means that there will be more operations, such as providing support to rescue injured civilian personnel in remote areas of the country, transporting citizens in times of calamity, or supporting humanitarian work.6

The Damascus Doctrine establishes Unified Land Operations (OTU) as the ENC’s operational concept, defining that the Force “capture, retain and exploit the initiative, which is executed through Decisive Action (offensive, defensive, stability and Defense Support to Civil Authority, ADAC) in order to create the conditions for a favorable resolution of the conflict” (author’s translation).7

OTU also highlights the necessary synchronization with other forces (joint missions), government agencies and institutions (coordinated or interagency missions), and multinational forces (multinational or combined missions) and the task, to the NCO, of “wide area security,” which is the application of the elements of combat power to protect the population, the troops themselves, infrastructure, strategic assets, and other activities.

Weapons of members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in a transition zone in Icononzo, Tolima Province, Colombia, on March 1, 2017. The UN Mission had begun verifying the handover of FARC-People’s Army weapons, in a process to be completed on May 29, 2017. (Photo: Jhon Paz/Xinhua/Alamy Live News).

The Brazilian experience

In Brazil, the evolution of land military doctrine has also been notable, in response to the new challenges imposed on democracies in South America since the early 1990s.

Based on the Constitution and reinforced by Complementary Law 97/99 and its amendments (LC 117/2004 and LC 136/2010), the Land Force acts with legal instruments throughout the national territory. Experiences, initially based on the Assurance of Law and Order (GLO), gained greater theoretical and practical reference as Brazilian society presented its diverse demands for security, motivated by diverse actors.8 Thus, it has expanded the range of operations of a subsidiary nature, showing itself flexible enough to adopt techniques and tactics proper to the national physical and human environments and, in particular, to the legality imposed by legal protocols.

General Eduardo Dias da Costa Villas Bôas, Commander of the Army from 2015 to 2019, used to say that the maturity of the Brazilian Army was based on legality, legitimacy, and stability.9 Without a doubt, this tripod was built on the solid doctrinal ground, whose fundamental aspect is the military schools, where the science and the art of warfare are the ultimate activities.

The doctrine of employment of the Land Force on national territory has undergone successive adaptations over the last three decades, with regard to the level of integrated action with other agencies. The issues of employment in support of public security, after ECO 92, together with the participation in Multidimensional Peace Operations, through the deployment of contingents of troops, were a driving force for the integration of the Army’s troops with other agencies present in the operational environment. This fact provided the use of lessons learned for the formulation of the doctrinal base for Operations in Interagency Environments and OCCA.

Peace Operations

In the meantime, the participation of Brazilian Peace Force Battalions in the 13-year mission in Haiti deserves special mention, as, among other reasons for its success, it integrated the conventional doctrine of military employment in urban areas with the perceptions of the psychosocial field of that environment, which some authors have labelled smart power.10 Brazilian troops acted in the most diverse crisis scenarios in the Caribbean country: security of elections, pacification of neighbourhoods, humanitarian support during natural catastrophes.

The Brazilian soldier who disembarked in Port-au-Prince in 2003 was adapted to a job with emphasis on the human dimension. His recent experiences in operations among the population, especially in the slums of Rio de Janeiro, made him familiar with the norms of personal conduct in operations, stricter rules of engagement, and adapted to the operational environment where collateral damage was not admitted. The Protection of Civilians was part of the troop’s culture, a fact that reflected the high level of approval of the troops’ conduct by the Brazilian population.

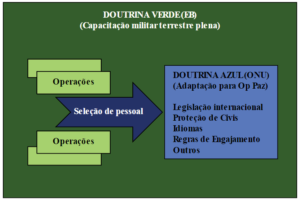

Figure 1. Blue Doctrine

On all occasions, however, the military’s readiness for a possible change in the application of the use of force was a sine qua non condition. Not by chance, Brazil has been invited to lead peace missions around the world and to hold decision-making positions in the structure of the Department of Peace Operations of the United Nations (UN). The judicious application of the “gradual use of force” concept, the interpersonal empathy (or even, “adjusted emotional intelligence”) and the Brazilian soldier’s common sense of really helping in the Haitian social transformation are some of the reasons for the operational success.

The Brazilian Joint Center for Peace Operations (CCOPAB), when training the last three battalions that went to Haiti (24th, 25th, and 26th), established the “Blue Doctrine” for didactic purposes, as a way of orienting the training of Brazilian troops under the “UN philosophy.

Considering that a significant number of the members of these battalions, at some point in their careers, had already participated in more than one operation of Global Law and Order or subsidiary, the adjustment to the rules of peace operations was made much easier.

The “Blue Doctrine”, in fact, adapted from the range of doctrinal knowledge established for the employment of Land Force, what was necessary for the application of the rules of engagement in a peace operation (see Figure 1). This broader framework, which aggregates both war and non-war, the CCOPAB called “Green Doctrine,” referring to the entire preparation process and its various nuances established by the Land Operations Command (COTER) in the annual Military Instruction Program (MIP).11

This case study confirms the assertion “he who does more, does less”, specifically about the application of the use of force, which is understood to be more restrictive in peace operations than in “conventional” conflicts.

The interagency environment

In 2013, the EB released Manual EB20-MC-10.201, Operations in an Interagency Environment. In it, the contemporary conflict environment (lato sensu) is defined as having:

- flattening of decision-making levels, bringing the political closer to the tactical;

- profusion of relevant technological capabilities among belligerents, both state and non-state;

- difficulty in defining lines of contact between belligerents;

- the tendency for confrontations to be protracted over time;

- presence of instant media in the battle space, prevalently influencing political decisions;

- appreciation of humanitarian issues and the environment;

- low acceptance among public opinion (national and international) of the use of force to resolve differences between peoples;

- exacerbation of the defense of minorities;

- The presence of non-governmental organizations in conflicts;

- Identification of information as a weapon, directly affecting the combat power of the belligerents;

- awareness that military forces do not solve the causes of war;

- the relevance of the population’s role in the fate of conflicts;

- prevalence of urban combat with the presence of civilians, against civilians, and in defense of civilians; and

- the difficulty of characterizing the opponent within the population.12

In this scenario, military commanders at all levels face an enormous challenge to operational performance, since the demands for information (about absolutely everything) have grown exponentially. This, in turn, is the “currency of exchange” of the main disruptive agents of order with their financial backers, and even with members of the media.

The presence of agents that were once strangers to the conflict scenario now becomes commonplace and often contrary to the legal forces sent to the places of friction. These agents, in turn, may effectively have ties with the area of confrontation, but they may also be external elements sponsored by the most diverse motivations.

It is also very common to exacerbate references to narratives that, in fact, have no direct link to the core of the friction to be solved, notably, psychosocial issues linked to exogenous ideological principles.

Cooperation and Coordination Operations with Agencies

In 2017, the Brazilian Army (EB) inserted in the manual EB70-MC-10.223, Operations, OCCAs as a new “basic operation”.13 The manual presents the following definition:

They are operations executed by elements of the EB with support to agencies or institutions (governmental or non-governmental, military or civilian, public or private, national or international), generically defined as agencies. They aim to reconcile interests and coordinate efforts to achieve converging objectives or purposes that serve the common good. They seek to avoid duplicity of actions, dispersion of resources, and divergent solutions, leading those involved to act with efficiency, efficacy, effectiveness, and lower costs.14

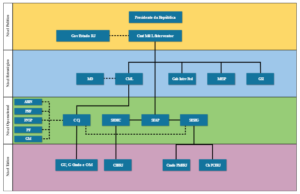

Figure 2. Command and control architecture and institutional relations

The Federal Interventor had under his command a series of agencies, whose common goal was to restore public security in the State of Rio de Janeiro.

In 2019, in the Fundamentals Manual EB20-MF-10.102, Land Military Doctrine, Land Force ratifies the protocols for acting in the “interagency environment,” which aim to facilitate the planning and conduct of military operations in the multicultural context.15

The manual points out that OCCA normally occurs in non-war situations, but may involve “actual combat” in the following “special” circumstances:

- (a) guarantee of constitutional powers;

- b) guaranteeing law and order

- c) subsidiary attributions;

- d) preventing and combating terrorism

- e) under the aegis of international organizations

- f) in support of foreign policy in time of peace or crisis; and

- g) other operations in non-war situations.16

In a first analysis, it is evident that the gradual use of force will adapt, together with the respective rules of engagement, to the environment of the conflict in which it will act. Notably, it is understood, for example, that “subsidiary attributions” and “preventing and combating terrorism” differ significantly, both in planning and in conducting the military operation itself.17

Another analysis is based on the premise that the level of agency action tends to vary according to the intensity of the fighting. The more hostilities, the less the agencies can contribute to supporting the population. Based on the principle of economy of means, the availability of agencies to act in support of civilians will impact to a greater or lesser degree on the availability of combat power against opposing forces. In this way, it is fundamental that the OCCA are conducted in such a way as to optimize the agencies’ capacity to act, allowing the military combat power maneuver pieces to be free to act in its core activity.

In this context, the maintenance of basic services for the remaining civilian population in the conflict area must be coordinated between the agencies and the military commander of the area, with the dual purpose of maintaining, as far as possible, the essential needs of civilians and avoiding the collateral damage of war among the people. All in order to maintain the support of the population and the national and international public opinion.

It follows that the OCCA doctrine can be applied in a war situation, on an exceptional basis, with its consequent degree of combativeness. From this premise stems the study now underway at EsAO, which aims to revise its Plans of Disciplines (Pladis), focusing on the integrated use of OCCA knowledge with the study blocks “Offensive” and “Defensive” (War).

The federal intervention in public security in the State of Rio de Janeiro

Major operations have also counted on the Army’s specific knowledge in support of security issues in Brazil: Eco-92, the Pope’s visit in 2013, the 2014 World Cup, the 2016 Olympics, GLO actions in Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo, among many others.

In a very unique way, the Federal Intervention in Public Security in the State of Rio de Janeiro was a remarkable experience in the application and validation of doctrinal military knowledge. The operation, in the non-war context, brought as an opportunity the expansion of the spectrum of smart power use, due to the occupation, by the military, of political and strategic decision-making levels of public power and, at the same time, the monitoring of the effectiveness of military and civilian actions with the population.

Officers and enlisted men participated in an unprecedented study, using purely their personal and professional experience allied to the security protocols of the State of Rio de Janeiro and the doctrine of operational planning common in the decision-making processes prescribed in military schools.

From a situation of near ignorance about the structure to be formed (in the case of the Federal Intervention Office) to those to be re-established (in the case of the public security agencies), significant results were achieved, not only operational and of immediate measurement, but also in the management practices of the agencies under intervention, embodied in several plans (strategic, social communication, and transition; see Figure 2).

The advent of the Federal Intervention in Public Security in the state of Rio de Janeiro was an example of the new demands that a crisis can bring to the Army’s sphere of employment. It was configured as an unprecedented demand for military commanders, with flattening between the political and tactical levels, besides the strong informational and human component.

The agencies’ capacity to act influenced the public opinion’s perception of the success of the mission, since only the availability of public agents would enable the implementation of government policies with lasting effect. The implementation of Quick Impact Projects (QIPs), a successful experience in Haiti, did not achieve the same results, increasing the pressure of public opinion on long-term structuring projects and making it difficult to maintain public support.18

For the first time in the last decades, a military commander assumed a protagonist role in managing the security of society in a delimited zone of action. Success in tactical actions against Public Order Disturbing Agents, in the physical dimension, would not necessarily guarantee victory in the informational dimension. The management of institutional relations with the agencies would be determinant to the success achieved by the Joint Command.

The case brought doctrinal reflection about the use of Land Force in a national environment, in a security crisis, acting in an interagency environment and with the use of force varying greatly, due to the proven firepower of the opposing criminal factions. In short, in certain locations of the operational environment, the combat took place with similar weapons on both sides, resembling the conventional paradigm, but under an unchanged legal framework, ruling out the state of exception, due to the context of normality of the nation as a whole.

Conclusion

Unless otherwise judged, the application by the Land Force of concepts consolidated for over 30 years in a legal and legitimate manner is of extreme value for the new paradigms of modern armed combat inserted in the context of “war”.

The experience of this indigenous doctrine, whose motto, “Strong Arm, Friendly Hand!”, draws the imaginary cover of its manual, is fully applicable to the current concepts studied by the military science of the 21st century.

To this end, the Fundamentals Manual EB20-MF-10.102, Land Military Doctrine, and the Campaign Manual EB70-MC-10.223, Operations, may in the future consider OCCA as “common actions in war and non-war,” allowing their planning and conduct in the broad spectrum of combat.

References

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and transl. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

- Peter Paret, Builders of Modern Strategy, tome 2, participation by Gordon A. Craig and Felix Gilbert, trad. by Joubert de Oliveira Brízida (Army Library, 2016).

- Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Concept for Operating in the Informational Environment, 25 Jul. 2018, accessed 4 Mar. 2020, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/concepts/joint_concepts_jcoie.pdf?ver=2018-08-01-142119-830.pdf.

- S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare (Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, October 2019), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-92.pdf.

- “FARC announces ceasefire amid Colombia peace talks,” YouTube video, posted by Telesur English, 19 November 2012, accessed 19 Mar. 2021, http://youtube.com/watch?v=Iv3kwZQtkWE.

- Gen (Reserva) Alberto José Mejía Ferrero, “Plan de Transformación: construyendo una Fuerza Multimisión,” Revista Ejército183, 8 Aug. 2016, accessed 19 Mar. 2021, https://issuu.com/ejercitonacionaldecolombia/docs/183web; “Veo un Ejército preparado para la consolidación de la paz,” Semana, 22 Apr. 2016, accessed 19 Mar. 2021, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/comandante-del-ejercito-alberto-jose-mejia-revela-futuro-de-la-institucion/470667/.

- Cel Pedro Javier Rojas Guevara, “Damascus: The Renewed Doctrine of the National Army of Colombia,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies17, no. 4 (June 2017), accessed 19 Mar. 2021, https://jmss.org/article/view/58266/43832.

- Brazilian National Congress, Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil (1988), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm; Brazilian National Congress, Complementary Law No97 (9 Jun. 1999), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp97.htm; Brazilian National Congress, Complementary Law No 117 (2 Sep. 2004), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp117.htm; Brazilian National Congress, Complementary Law No 136 (25 Aug. 2010), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp136.htm.

- “EB’s Pillars for Addressing the Current Political Crisis: Stability, Legality, and Legitimacy,” Defesanet, 24 Mar. 2016, accessed 4 Mar. 2020, https://www.defesanet.com.br/crise/noticia/21949/Os-pilares-do-EB-para-enfrentar-a-atual-crise-politica-Estabilidade-Legalidade-e-Legitimidade.

- Johanna Mendelson Forman, Investing in a New Multilateralism. A Smart Power Approach to the United Nations, Center for Strategic and International Studies (January 2009), accessed 4 Mar. 2020, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/090128_mendelsonforman_un_smartpower_web.pdf.

- “Blue Doctrine” was the term created by the author, when in command of the Brazilian Joint Center for Peace Operations (CCOPAB), in order to facilitate the understanding, by external actors, of the preparation of Brazilian troops for peace operations.

- Army Staff, EB20-MC-10.201, Operations in Interagency Environment (Brasília, 2013), 2-1 to 2-2.

- Army General Staff, EB70-MC-10.223, Operations(Brasília, 2017).

- Ibid.

- Army General Staff, EB20-MF-10.102, Land Military Doctrine(Brasília, 2019).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rapid Impact Projects: established by elements of the civilian component in UN peace missions, with executive support that also includes the military component. Successfully used in MINUSTAH by Brazil’s Peace Battalions, in line with tactical activity.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency of the U.S. government, Diálogo magazine, or its members. This Academia article was machine-translated.